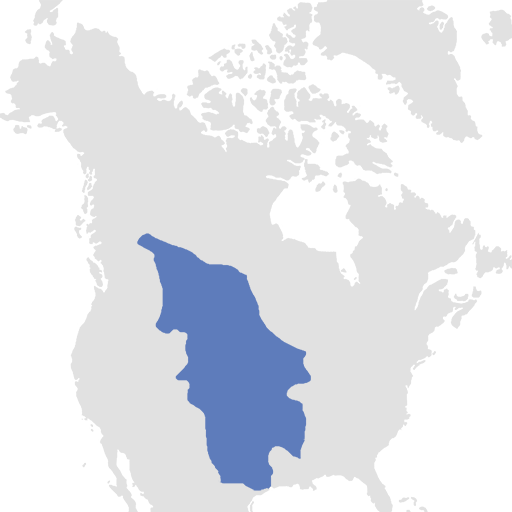

The Great Plains and Canadian Prairies

When thinking of native North Americans, the image formed for most people will be of an indigenous person from the Plains area. The art from this area has become iconic, from feathered headdresses to tipis. Smoking pipes are another quintessential object linked to the Plains. While pipe smoking took on a ritual and religious importance for many groups throughout North America, the most famous are the long calumets, or “peace-pipes” of the Plains regions.

The most favoured stone for carving pipe bowls was Catlinite, also called pipestone. A type of reddish-brown argillite, it gained its name when the American traveller and painter George Catlin visited a quarry in Minnesota in 1835 and brought back a sample for scientific analysis. Pipe bowls would be carved out of this smooth mineral originally using flint or other suitably hard material. Steel tools introduced by European traders were used later.

The wooden stems attached to the pipe bowls could be quite long, sometimes over a metre in length for ceremonial purposes. Both the pipe bowl and stem were endowed with sacred power. Indigenous people believed that when the two parts were brought together, the power of the pipe would be activated.

Women of the Plains were highly skilled and produced exquisite clothing through the preparation and decoration of hides. Men, women and children would be adorned with items derived from or modelled from the natural world. Like many areas throughout North America, decorative quillwork was prevalent until the introduction of glass beads in the early 19th century which in turn led to new stylistic developments. Women of skill and dedication routinely crafted objects that were not only beautiful, but also in harmony with their environment.

Many groups and tribes on the Plains were forced onto reservations by the end of the 19th century. The “enforced leisure” of reservation life led to an increased richness of women’s artistic traditions as they had more time to devote to their skills. Subsequently, beadwork blossomed and items of clothing such as dresses, vests and moccasins were decorated all over with beaded designs.

Expressing identity and achievement through decorating the body and possessions was one of the most important functions of native North American art. This can be seen in the exceptional examples of beaded bandolier bags, a dress ornament that became more symbolic than functional.

Parfleche containers were also a highly artistic form of bag made by Plains peoples. Made of tough rawhide, these sturdy bags were used to transport a variety of materials including clothing and food. A parfleche may have been a very practical implement but they were lavishly decorated with brightly painted geometric designs.

The warlike spirit of the Plains peoples was motivated by honour, not wealth. Their nomadic way of life meant material wealth was a hindrance, and the gaining of territory was only of marginal interest in a land that was vast. Prestige came from tribally sanctioned war which focused on Scalp raids, where enemies would be killed and scalps taken, and Horse raids which targeted the capture of horses.

From the 1850s, warfare changed as Plains groups became embroiled in a slow war of oppression with the forces of the US government that brutally ended in 1890 at Wounded Knee.

A variety of weapons would be used during warfare. Guns were introduced to the people of the Plains firstly by native groups further East and then directly from contact with white European traders, but traditional weapons such as clubs and bow & arrow were widely used. The bow and arrow in particular were useful weapons when hunting buffalo.

Providing shelter for many peoples across the Plains regions, tipis were made from several hides and skins- it could take over 12 buffalo hides to make a tipi. Tipis were made by women. For such a large-scale task, women would work collectively as a group to produce them, with specialists performing particular tasks. Certain aspects of skin and hide work were very specialised indeed and women could earn stature and wealth through their art.

By the turn of the 20th century, the production of tipis had practically ceased. Massively declining buffalo numbers meant that hides were not readily available, and the enforcing of indigenous Plains peoples into reservations marked the end of the nomadic way of life that the tipi was designed for.