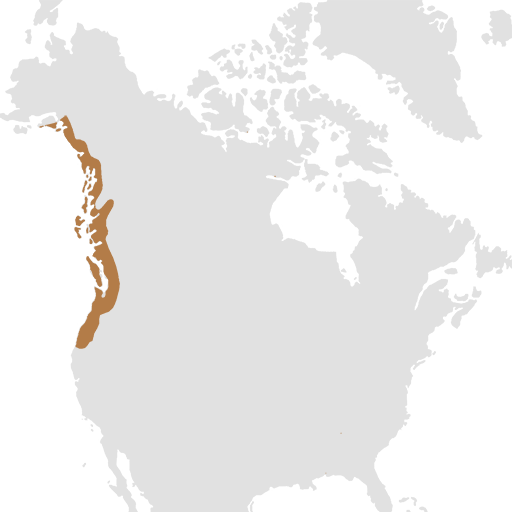

Pacific Ocean to the west and the Rocky Mountains on the east

While Haida carvers had been sculpting their exquisite pipes since before the arrival of Europeans, argillite crest poles were a later development. They were modelled from the original huge cedar crest poles such as the type that were erected outside of houses. Like these monumental structures, the argillite poles displayed the carver’s crests or depicted stories and legends, the meaning of which may be lost to us now.

These poles began to be produced in the second half of the 19th century at a time when the large cedar crest, or “totem”, poles were no longer being made. They were seen as “heathen” and depraved by missionaries and government officials, and the 1884 amendment to the Indian Act effectively banned the raising of any new crest poles. Like the argillite pipes, the miniature crest poles helped the Haida to keep their traditional stories alive and tourists eagerly collected these wonderful sculptures.

While argillite was unique to the Haida, many other Northwest coast groups carved miniature totem poles from wood. These too show an adaption to the region’s changing economic and social conditions. Both argillite and wooden poles were at one time dismissed as “tourist art”, products of the degeneration of Northwest culture. Today, we can see that these poles are still resonant with traditional cultural elements. They help to narrate a history of a past colonial age and demonstrate a complex process where both white European control and native creativity occur.

Argillite pipes first began to appear in the west in the first quarter of the 19th century. Previously, ships from Europe had only been interested in the sea otter pelts that the Haida people traded with. By the early 19th century however, sea otters had been heavily hunted and as their numbers declined, pelts became scarce. It was at this point that European traders and visitors to the Queen Charlotte Islands noticed the Haida’s material culture, in particular their argillite pipe carvings.

Argillite is a black coloured mineral that is unique to the Haida islands, with a high water content which made it an excellent material for carving. It is thought that the Haida had been carving argillite pipes well before first contact with white Europeans, probably for use by shamans. It is unlikely that they were used for smoking with however, the shaman possibly using pipes in ritualistic ways during winter ceremonies. Haida craftsmen followed ancient practices to carve out the pipes which contained images of animal and supernatural figures that featured in Haida legends and stories. As beautiful sculptures, the carvings were seen as “art” in the West and a brisk trade in the pipes began.

Throughout the 19th century, the pipes evolved and were carved into different forms, and visitors continued to purchase them. As disease took its toll on the Haida population, the traditional way of life was being eroded as forced cultural assimilation by the Canadian government began. Tourists to the islands bought more Haida art as it was feared their culture was seemingly on the verge of disappearing. Argillite pipes would enter museums around the world and keep the Haida’s traditional stories and art forms alive.

While serving as vessels for holding food, bowls were also symbols of wealth and prestige for Northwest coast peoples. Crests may form the decoration at the ends of the bowl or the bowl itself may be carved into the shape of an animal.

During feasts, rich foods including eulachon oil were often served in dishes which led to their name of “grease bowl”.

Original house entrance poles were a type of crest pole and could be anywhere between about 6 - 12 metres in height. Often, there would be an oval shaped hole at the bottom of the pole that served as a door. This was only used on ceremonial occasions however- there would be other entrances into the house for everyday use. Models of great Haida houses began to be produced by the end of the 19th century, and they became a favourite souvenir for tourists. No single complete original Haida dwelling now survives, so house models provide an important historical record .

Some of the most stunning art of the Northwest coast can be found in the diverse array of masks and headdresses from the region. Masks were used in rituals and ceremonies, including the Potlatch, where dancers would perform and enact mythical stories.

Masks could take the form of a human face, an animal or a supernatural creature. They were manifestations of powerful ancestral spirits and their use was to make the supernatural world visible. During elaborate staged performances, a magical past would be recreated with the help of masks. When used by a skilled dancer, a mask would assume an intense character.

From the 1820s, masks began to be made for sale to Europeans and Americans rather than for cultural usage. In 1884, an amendment to the Indian Act barred potlatches which led to many masks being confiscated and collected. Despite the new law, many new masks were created in a bold attempt to hold vital ceremonies and rituals in place which would help many First Nations peoples define their place in the cosmos during a period of enforced cultural assimilation.

Mats were used in the daily lives of Northwest coast peoples in many ways. They were practical objects that could be placed strategically within houses to prevent drafts or used as cushions to kneel on when cleaning fish. They were also used for ceremonial occasions when they could be used for seating at feasts and given as potlatch gifts.

Mats were woven by women. Designs ranged from simple stripes, to more complex patterns, and could even have painted images. Painted mats can be found in many museum collections around the world, as these types of mat were often produced for the tourist trade.

Clubs were used in the Northwest during combat, to dispatch animals when hunting and for ceremonial purposes. Both clubs featured in the Great North Museum: Hancock collection are rare and early types. It is likely that clubs were widespread along the Northwest coast in the 18th century with many of these early examples being acquired at Nootka sound- possibly due to trade occurring in this area.

Rattles were integral to many ceremonies throughout the Northwest coast. While some rattles were used by chiefs and clan leaders, they are closely associated with shamanism. Shamans were powerful people who could transcend the boundaries between the human and spirit worlds. They could communicate directly with spirits to help heal people and foresee events. Each shaman had a spirit helper or helpers and rattles were used to induce a trance state within the shaman and summon these helpers. Whenever a rattle was used , a supernatural presence was thought to be in attendance.

Rattles were produced in various decorated states. Some were plain with few elaborations, while others, such as raven rattles, were more lavishly decorated. Shamanic objects such as rattles were imbued with great power. Because of the danger these objects could pose, they were often buried with the shaman on his/her death away from villages.